Add Editore has provided the opportunity to interview Eleanor Davis, one of the most eclectic and interesting comic artist in the American contemporary landscape. Her Why, art? stads for a philosophical manifesto on the concept of art at artist’s service. In this interview Davis guides us with the hand in her creative world, by commenting her most important graphic novels.

Hi Eleanor and welcome to Lo Spazio Bianco, we are extremely happy to have you here. Many thanks also to add editore, Italian publisher of Art Why? that put us in touch.

So happy to get to talk with you!

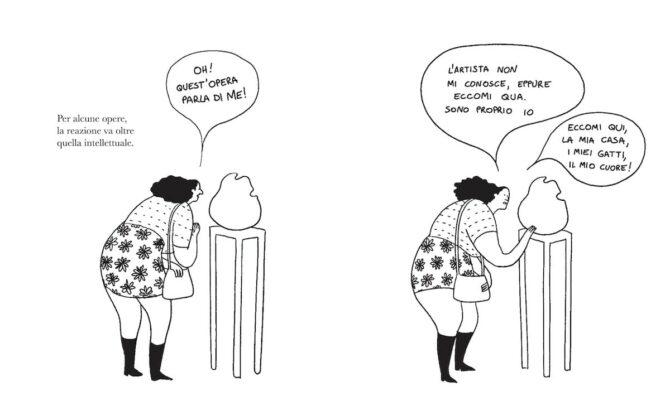

Let’s start exactly from there. Art Why? stands for a philosophical journey trying to explain the several and different implications of art and the reason why people are pushed to create that. How was the idea of this project born?

Why Art? started as a keynote presentation I gave at ICON9, an illustration conference here in the US. That kind of space tends to be both very commercial & anxiously concerned with the importance of what we do as illustrators beyond commercialism, so I wanted to kind of explore that and maybe make fun of it a little.

In the work you are using an images’ path over comics and illustration. How do you place yourself as an artist against those two images related narrative processes?

I don’t have a strict separation in my mind between comics & illustration. What I do have is a strict separation between art I do for money – which is usually single-image, but not always – and my personal work which is a mix of single-image, sequential, wordless, and including words. The main difference for me between illustration & comics is that comics are more work; they have less flexibility.

In Art Why? no real answers are given to the question in the title, rather some considerations come up with the aim of amplifying the concept. Is it really impossible to give it an answer?

For me Why Art? was as vociferous an answer as I can possibly give! I feel like I really came out swinging with it! The Hard Tomorrow, which is supposed to be a dystopic tale, actually turned into a reality (almost!) of what was happening in the US: how did you feel while all that was happening? How was your perception of it and what was the influence that the real facts were having on your work?

The Hard Tomorrow, which is supposed to be a dystopic tale, actually turned into a reality (almost!) of what was happening in the US: how did you feel while all that was happening? How was your perception of it and what was the influence that the real facts were having on your work?

I wrote The Hard Tomorrow in 2017 and finished it in 2019, and although it was about an America that was maybe a little bit worse, it wasn’t very much worse. All that kind of stuff had been basically going on at some scale for forever. The march & arrests in The Hard Tomorrow were roughly based on a night march I had been to, I think, in 2014 (?) in downtown Atlanta, where a huge number of riot police kettled us & arrested a bunch of people. The Black Lives Matter protests & corresponding police violence in the Summer of 2020, right after the book came out, was just a larger more visible version of what had already been happening. Of course I celebrated the protests and protestors but watching the state violence play out the way it did was nothing but horrifying and heartbreaking. When you write dystopic fiction the last thing in the world that you want is for it to become true.

The last 5 figures of the graphic novel, mutes and alike apart from a very particular details, stand for a very positive and optimistic ending, and represents a challenge to the world, too. That same world that does not seem to have improved or maybe it is even getting worse quicker and quicker. So, do you really think that the only way to resist and be brave is to entrust all our hope in our children?

In 2015 when my husband and I decided to try to have a baby I said they would be “a fragile piece of kindling to be added to this fire.” We finally had a baby in the Summer of 2019. And the fire just keeps getting worse then.

It’s a constant cause of frustration & embarrassment to me that so many people interpret the ending of the Hard Tomorrow as being optimistic. Hopefully with my next book I won’t fuck up so badly. Of course a baby is a wonderful thing. But a baby is not a concept, it’s not something for old, tired, frightened people to project our weird intense hopes and sorrows onto. A baby is a human being, brand new, helpless, with no control over the world into which they have been born. They aren’t somehow separated from our weird crumbling mess. They are deep in it. In How to be happy, your book of short stories, you use colors and different techniques, while in The Hard Tomorrow and Art, Why? You preferred the black and white solution or rare monochromies. What’s it for you to use one technique or another? What are the different creative opportunities? Why did you choose to reduce the colors to the very minimum in your last work?

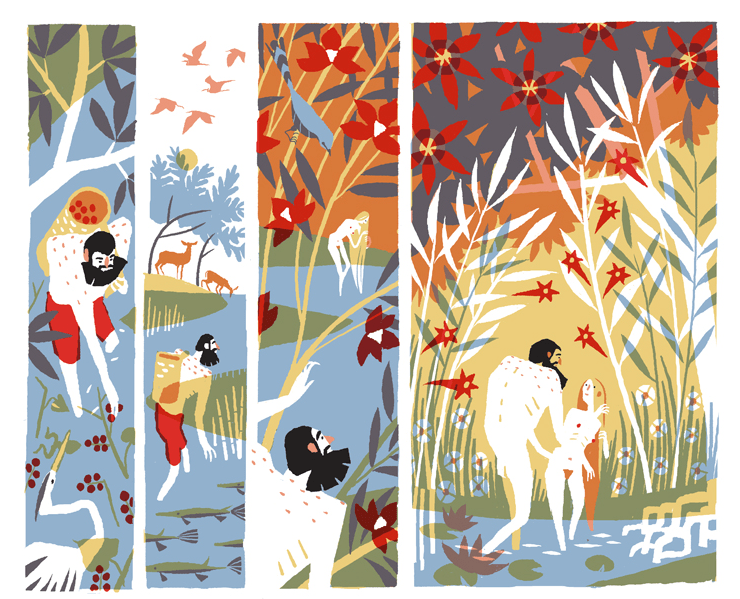

In How to be happy, your book of short stories, you use colors and different techniques, while in The Hard Tomorrow and Art, Why? You preferred the black and white solution or rare monochromies. What’s it for you to use one technique or another? What are the different creative opportunities? Why did you choose to reduce the colors to the very minimum in your last work?

I like black and white linework aesthetically and it’s a lot easier to do. I am better at line than shape, and color tends to drown out the line in a way that really bugs me. However, black and white is kind of by definition really, well, black and white – there is a lot of subtlety that gets lost, especially with skin tone and by extension race. That’s something I’m still trying to figure out. Maybe color is the only real solution.

In all your comics, the characters have unproportioned heads compared to their solid and at the same time light bodies, due to the sinuous outlines. This feature is often present in the contemporary women’s comics scene, as for instance by Lee Lai, Tommi Parrish and also the Italian Zuzu. What is the reason behind this choice?

I think it looks cool. I personally have a very small head. (I don’t think Tommi identifies as a woman btw!)

I suppose I think a small-head style could be in opposition to a bighead style which is about infantilization, pre- or asexuality, cuteness, mental over the physical.

How does this style speak to the wider consideration on bodies that takes a big place in your works, especially in The Hard Tomorrow?

I guess I really like bodies! They are interesting, and people are weird about them, we have a lot of intense desire and pain and fear around our own bodies and the bodies of other people. We live in our bodies and we are our bodies. And they are fun to draw. In some ways comics are inevitably more about exteriority than prose often is. So I am trying to get at something inside by drawing what’s outside.

Your comics face very important contents, swinging from tragic moments to more ironical scenes. The ending provides always a vision of hope, not in terms of entrusting the Providence, but rather a real and active hope: is this the ultimate goal of your art and your comics?

I do kind of agree with this, which is kind of weird since I just kind of crankily insisted that the ending of The Hard Tomorrow isn’t supposed to be hopeful (it isn’t). But also it isn’t supposed to be hopeless. To me, writing something hopeless is like shooting fish in a barrel. Half the stories I come up with in my head are totally hopeless. They are nothing but drawn out “life sucks and I’m going to prove it” exercises in self-harm. I don’t ever finish these stories. What’s the point? I don’t believe that kind of thinking is true, or helpful to myself or other people, or interesting, or beautiful, or complex, or funny. I think a good story should be complex and a little funny, like life is. A good story should have some space in it. And space, I think, feels like hope.

Thank you again for interviewing me! I am really honored to get to be interviewed by Lo spazio bianco. All the best, and I hope you and yours are well.

Eleanor Davis is an American comic artist. She published some short stories in How to Be Happy and two graphic novels for kids: The Secret Science Alliance and Copycat Crook (2009); this last one was created together with her husband Drew Weing. The Hard Tomorrow and Why, Art? are her last graphic novels. Davis is also illustrator and comic artist for The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time Magazine and many others. She lives with the family in Athens, Georgia.