Active for more than thirty years on the U.S. underground comics scene, Johnny Ryan is a cult author appreciated all over the world. Irreverent, exaggerated, politically incorrect and without limits since his debut with the self-produced seriesAngry Youth Comix (noticed by the dean of indie authors, Peter Bagge, who proposed him to Fantagraphics), over time Johnny Ryan has created satirical, science fiction, fantasy comics, on paper as well as online, always maintaining a good dose of pure underground anarchy.

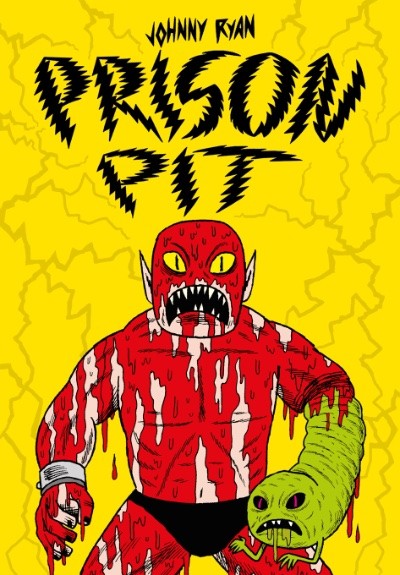

With Prison Pit, a hyper-violent comic book, a sort of Mad Max on acid, he reached planetary success. Guest at Napoli Comicon for Eris Edizioni, which in 2019 translated the complete Prison Pit into Italian, we interviewed him to learn more about this work but also about underground American comics, yesterday and especially today.

We thank Valerio Stivè for his role as interpreter during the interview.

Hello, Johnny. Welcome to Lo Spazio Bianco and thank you for your time. Almost none of your works have been translated in Italy, but Eris Edizioni published a few years ago the complete edition of Prison Pit, your most well-known work all over the world. Let’s start from the easiest question of all: how was the idea of this work born?

Hello, Johnny. Welcome to Lo Spazio Bianco and thank you for your time. Almost none of your works have been translated in Italy, but Eris Edizioni published a few years ago the complete edition of Prison Pit, your most well-known work all over the world. Let’s start from the easiest question of all: how was the idea of this work born?

At that moment I got tired of the kind of comics I had been doing up to that point and I thought I would start working on a series, so that I would be committed to a project for the next five or ten years. And I immediately thought of an action story that also contained a lot of violence.

Before Prison Pit what were the comics you were creating like?

For a few years I had been working on another series called Angry Youth Comix, which was originally published as a three-volume set, and I was also doing short stories for Vice.

Prison Pit, in some moments, reminds of Mad Max movie on acid. What were the inspirations for the post-apocalyptic setting and the punk tones of the series?

I had two fundamental inspirations: one was Powr Mastrs by C.F., another series in small fantasy-generating and rather weird albums, with an authorial and minimalist approach; the other is Berserk by Kentarō Miura, a manga of which I have always appreciated the fantasy context but at the same time hyper-violent, in which things gradually become more and more absurd and are still taken extremely seriously.

Speaking of Kentarō Miura and Japan, following your Instagram account in recent times, I noticed that you are a big fan – in addition to alternative comics – also of Japanese photographers. Is this interest reflected in any way in your works?

Rationally I would answer no, but how can I be sure? How can I exclude that those works, entering my head, are reflected in what I write and draw? As Stanisław Zukowski argued, an artist is like a dog looking for food from various garbage cans and feeding on what it finds.

Coming back to Prison Pit, what did it mean for you, also from a practical point of view, to create a saga that developed in so many years?

In order to start and carry out such a long work, I first of all put a lot of determination into it. But then, in practice, I didn’t follow rigid and preset schemes, because I prefer to work by assembling images and following suggestions. And this means that if sometimes I found myself rethinking, adding or eliminating something, I might as well follow my instincts and do it.

How was Prison Pit initially received and when did you realize it was becoming a cult film, at least initially in the States?

How was Prison Pit initially received and when did you realize it was becoming a cult film, at least initially in the States?

At first I was concerned that someone in my fanbase – if you can call it like that – who was really passionate about my early material and the comic stories I had done up to that point, might be alienated by the new direction I was taking my work. And I don’t rule out that there are still, among my readers, those who prefer my early stories. In fact, I noticed from the very beginning that Prison Pit was taking root, acquiring more and more readers, and being appreciated more and more.

In spite of this, I have difficulty in defining Prison Pit as a “popular” product as Star Wars can be, which is true pop culture. But seeing it land in Europe, translated in more and more countries and realizing the growing interest of new publishers and readers made me realize that I was doing something really successful and appreciated.

This was confirmed when Prison Pit was also translated in Russia and I was guest at a festival in St. Petersburg: the work was so well received by the public that I was impressed. Realizing that I had approached a culture that I had always considered very distant from my own and not interested in what came from the United States made me realize that I had done something really good.

The stories contained in Prison Pit, as we said before, are full of violence and extreme images. In order to allow you to publish them, how important was the support of Fantagraphics? Did they or other publishers that translated or distributed you in other countries ever have doubts that some stories might too “strong” to be published, or on the contrary they always left you freedom about it?

Fantagraphics has never given me any kind of problem, they have always been very open to my vision. And, if possible, foreign publishers have been even more open-minded, maybe because they see the US as the “Land of freedom” and, from a certain geographical distance, they are very interested in my and other artists’ non-conformist approach.

If anything, the problem with Fantagraphics arises now that I’m working on a new project. When I showed it to them there was some fear that this book might cause me and them some problems. I am referring to certain images and certain jokes that I use. This is because for some time now there has been a change in the approach to the themes of race and sex that, if portrayed in a “rough” way, are not well seen. Violence is an issue that in the context of fiction is still accepted, while the approach to other issues must somehow be mediated to conform to the vision we have of it today.

Which is rather odd when we think that Fantagraphics is the publisher of Robert Crumb’s complete works…. But an author like him is somehow “absolved”, because his work is contextualized in a past historical moment, different from ours, which leads us to think something like “they are old, in their time they didn’t understand”. Now it is necessary to have a greater awareness and this awareness must be demonstrated.

Let me try to interpret what you mean: after Me Too and the Black Lives Matter movement, has anything changed in the world of culture, art and comics?

Absolutely yes, a lot has changed. Just think that before this cultural revolution we have memory of only one author who has come up against a sort of censorship by the U.S. government for obscene representations and that is Mike Diana, who, because of the content of his works, was convicted of obscenity and forced to probation for three years.

In the 1990s, when Diana was convicted, the idea of being “against”, of acting against the establishment, was very present. Now, instead of fighting conformity, people are creating it through the internet. We live in a virtual bubble in which we gather and decide what is good and what is not, what is correct and what is not. And after that popular judgment, after the media lynching, if you did something wrong according to the common sentiment, you may no longer be able to work and make money from your work.

I’ll ask you one last question before saying goodbye and I thank you again for your availability for this interview. You have been in the world of alternative and underground comics for over twenty years now. What do you think has been the biggest change in this environment in these years? What do you think about today’s alternative comics?

The way I see it, something has definitely changed. Several years ago there was, in the alternative comics world, the idea of going in the direction of art comics. A type of comic book of a certain level that, following the success of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, many felt entitled to create a comic book that could win awards and be considered drawn literature. In that context an elitist spirit was born in the world of comics that, personally, did not concern me at all: when I started and, even after, my only interest was to create a funny and hilarious comic, that was my way of being “different”.

Nowadays there is no longer, perhaps, an elitist idea of comics, replaced by that bubble we were talking about earlier, derived from a certain conformism dictated by a sort of self-control that comes from what the Net, as a self-determining extended community, indicates to do or not to do.

Interview realized on April 23, 2022 during Napoli Comicon.

Johnny Ryan

Born in Boston, Johnny Ryan is one of the most important authors of the American alternative and independent comics scene. He started working in the ’90s, self-producing his works and quickly becoming one of the essential artists of theUS and international underground scene. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

His comic book series such as Angry Youth Comix, Blecky Yuckerella and Prison Pit, have received many awards from the public and critics. He has collaborated for years on joint projects with the likes of Dave Cooper and Peter Bagge, and has worked for many of the major brands in the world of television animation (Warner, Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network). His work has appeared in numerous magazines such as MAD, LA Weekly, National Geographic Kids, Hustler Magazine and The Stranger. Prison Pit, his first work to be translated in Italy, is his most famous series in the world: it has been translated into many countries and, in addition to being turned into action figures, has also been transposed into animation.