You can pick and choose the Superman of the moment in any of the strains of re-interpretation or selective homage we’ve talked about in the main essay here. But Tom Scioli’s Satan’s Soldier (an ongoing webcomic collected into a series of physical minicomics) is one sprawling instinctual dissertation on the complete raw material of what Superman can mean.

You can pick and choose the Superman of the moment in any of the strains of re-interpretation or selective homage we’ve talked about in the main essay here. But Tom Scioli’s Satan’s Soldier (an ongoing webcomic collected into a series of physical minicomics) is one sprawling instinctual dissertation on the complete raw material of what Superman can mean.

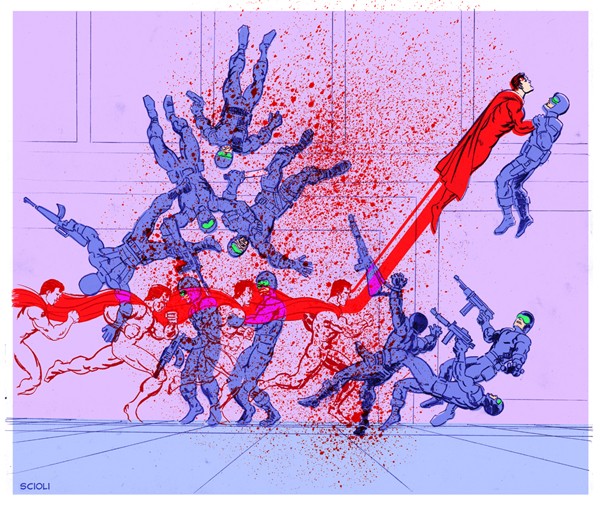

A distorted and revealing reflection of all eras and implications of the Superman we know, Soldier is a red-suited, devil-colored anti-deity with a pentagram inside his chest insignia making it resemble an unbreakable diamond or hellish glyph. He rampages across reality like a heedless behemoth; Scioli has said that, to a being who can see through mortals’ bodies and outpace them at super-speed, the world and all its lifeforms would seem like a dream, to be remade and discarded at whim, and this is not the malice but, more frighteningly, the nature of Satan’s Soldier slimming supplements.

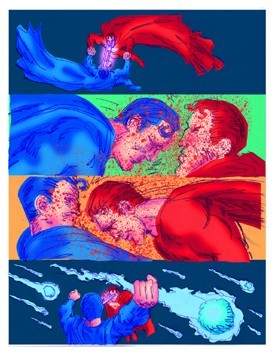

As he shatters planets in a conflict with his blue-suited opposite it’s like watching a natural history of the divine; not higher beings but just bigger, with a fundamentally terrifying subtext for what the idea of gods really signifies — not ideal versions of ourselves, but primal movers and shakers inspired by some racial memory of prehistoric beasts. If this is what waits for us in upper dimensional planes or “the future,” then it’s best to stop moving, but our ant-like pace is of no notice let alone concern to the beings of this series.

As he shatters planets in a conflict with his blue-suited opposite it’s like watching a natural history of the divine; not higher beings but just bigger, with a fundamentally terrifying subtext for what the idea of gods really signifies — not ideal versions of ourselves, but primal movers and shakers inspired by some racial memory of prehistoric beasts. If this is what waits for us in upper dimensional planes or “the future,” then it’s best to stop moving, but our ant-like pace is of no notice let alone concern to the beings of this series.

Every trope from every era of Superman himself is represented, and every variant is intuited (Scioli confesses to unfamiliarity with some creepy biological and theological themes from The Boys and Irredeemable, respectively, that play a role here); even every related association — like the reducing of the “blue” superbeing to a Christopher Reeve-like paraplegic — is included.

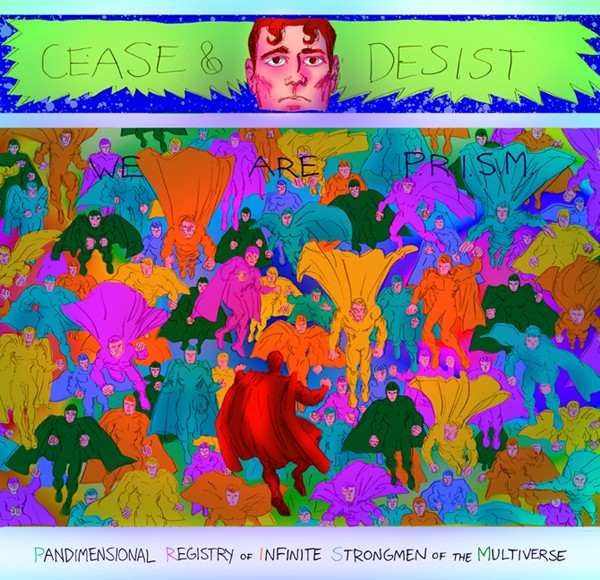

Scary, elemental archetypes of the refashioned pagan pantheon that grew up around Superman — the Hades-like Batman improvisation d’Ark, a Cthulhu-ish counterpoint to the Martian Manhunter called Invader, etc. — make this feel both like some modern system of superstition (not the redeeming “myth” that we think makes our imaginations superpowerful), and also the worst nightmare of corporate creativity machines — in the weird thematic mashups and absurd wordplay these characters exhibit (history, religion, national mascots, comics and consumer goods collide in “Lollipop Lincoln,” “Cosmoses” and “Union Jack the Ripper”), Scioli portrays a kind of cross-contamination of ideas that represents the twilight of copyright in a way that must terrorize entertainment businesses — and of course stirs in the central meta-text of Superman’s 75-year run: the original sin of his theft from his creators.

Scary, elemental archetypes of the refashioned pagan pantheon that grew up around Superman — the Hades-like Batman improvisation d’Ark, a Cthulhu-ish counterpoint to the Martian Manhunter called Invader, etc. — make this feel both like some modern system of superstition (not the redeeming “myth” that we think makes our imaginations superpowerful), and also the worst nightmare of corporate creativity machines — in the weird thematic mashups and absurd wordplay these characters exhibit (history, religion, national mascots, comics and consumer goods collide in “Lollipop Lincoln,” “Cosmoses” and “Union Jack the Ripper”), Scioli portrays a kind of cross-contamination of ideas that represents the twilight of copyright in a way that must terrorize entertainment businesses — and of course stirs in the central meta-text of Superman’s 75-year run: the original sin of his theft from his creators.

The looseness of Scioli’s rendering and kirlian singe of his colors is a cauldron of inventiveness, the raw elements of these ideas barely contained by any defining line, while what he puts on the page is endless movement, pure (or vitally impure) possibility. In the same way, these dreaming storylines feel like the uncut psychic underlay of decades of comics, the molten core of essential anxieties and impulses, a surreal drama somewhere between the psychedelic pulp of Dom Regan and the sketched-in spectacle of Frank Santoro. Superman can’t be contained, by stone walls or prescriptions of personality or edicts of corporate characterization — but in Scioli’s hands he is more reshapable than anyone could dream or dare.