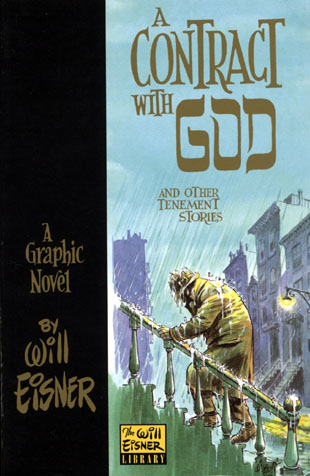

The Spirit is willing and his flesh is scarcely a consideration, as he places himself repeatedly in mortal peril and endures extreme physical punishment in the course of prevailing against his foes. The devout man in A Contract with God eventually rejects a divine order he feels has abandoned him; Denny Colt never counted on it to begin with and seems much less barred from getting on with life (or in his case maybe, afterlife). Certainly the 1940s/’50s context of the original Spirit strip provided a more self-assured American profile than the beleaguered mid-to-late 1970s in which Contract came out (even though it too was set in the early 20th century). But more significantly, the Spirit places trust — faith, one might even say — in the rules not of God but of humankind; the law. This is a code set up by mortals to maintain a civilization, though it does echo a more Hebrew conception of God — not the all-powerful Christian force who makes you guarantees, but the, indeed, contractual being who sets the terms by which you are then expected to conduct your own life.

The Spirit’s cases were not just episodic incidents in a continual string of dangers and battles like much of adventure fiction; they were self-contained vignettes, the graphic equivalent of the short story or the one-act play. Eisner borrowed the visual techniques of noir cinema and innovated compositional motifs of art-comics that extend into the present day (like the architectural layout of a panel-grid, so associated with Chris Ware). Narratively, the Spirit was a figure who events acted upon; a servant of The Law, he was there to be the wall that wrongdoers run into, not to guide events himself.

That was the fatalism of a generation that didn’t know how it had survived the Great Depression or made it back from World War II, and Denny Colt, vulnerable, unserious about himself, is a revealing alternative to the more official, imposing models of masculinity from the period, and a refreshing presentiment of a later era’s values.

This is the confessional mode of Jules Feiffer (who, not coincidentally, assumed an increasing creative role on the strip as an assistant and then collaborator after Eisner came back from WWII service); the verisimilitude of modern-day graphic memoirs; the brevity of webcomics that unfold in compact individual chapters. It’s not something that Eisner emerged into in the late 1970s, but rose through almost from the start.

The insight of the Spirit, that you must be an individual but you can’t act alone, and his awareness, as one who has faced mortality and sees into other’s fears, is the nature of a heeded or ignored conscience, the knowledge of a god — but God the father, not your keeper. In the 1940s, and no less at the end of his life, Eisner and his heroes were there in spirit, but they knew that God probably wasn’t listening, and it might be best to write a story of our own.