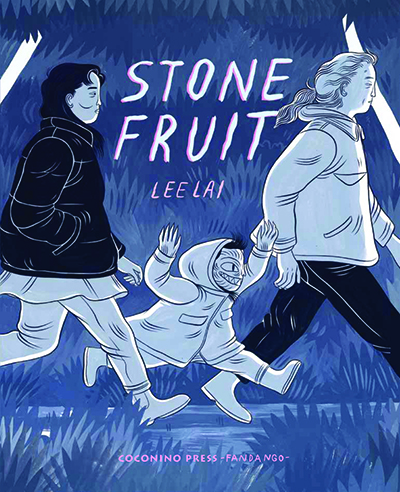

When Stone Fruit was released in 2022, no one yet knew the transgender and homosexual author Lee Lai, but her impact on the comics world was explosive. The story of a lesbian couple and their intense relationship with one woman’s young niece dug deep into our society, exploring interpersonal and family relationships — both biological and chosen — while also addressing questions of ethnic and gender identity, sexual orientation, and the everyday life that, through Lai’s touch and a kind of magical realism, became something extraordinary.

When Stone Fruit was released in 2022, no one yet knew the transgender and homosexual author Lee Lai, but her impact on the comics world was explosive. The story of a lesbian couple and their intense relationship with one woman’s young niece dug deep into our society, exploring interpersonal and family relationships — both biological and chosen — while also addressing questions of ethnic and gender identity, sexual orientation, and the everyday life that, through Lai’s touch and a kind of magical realism, became something extraordinary.

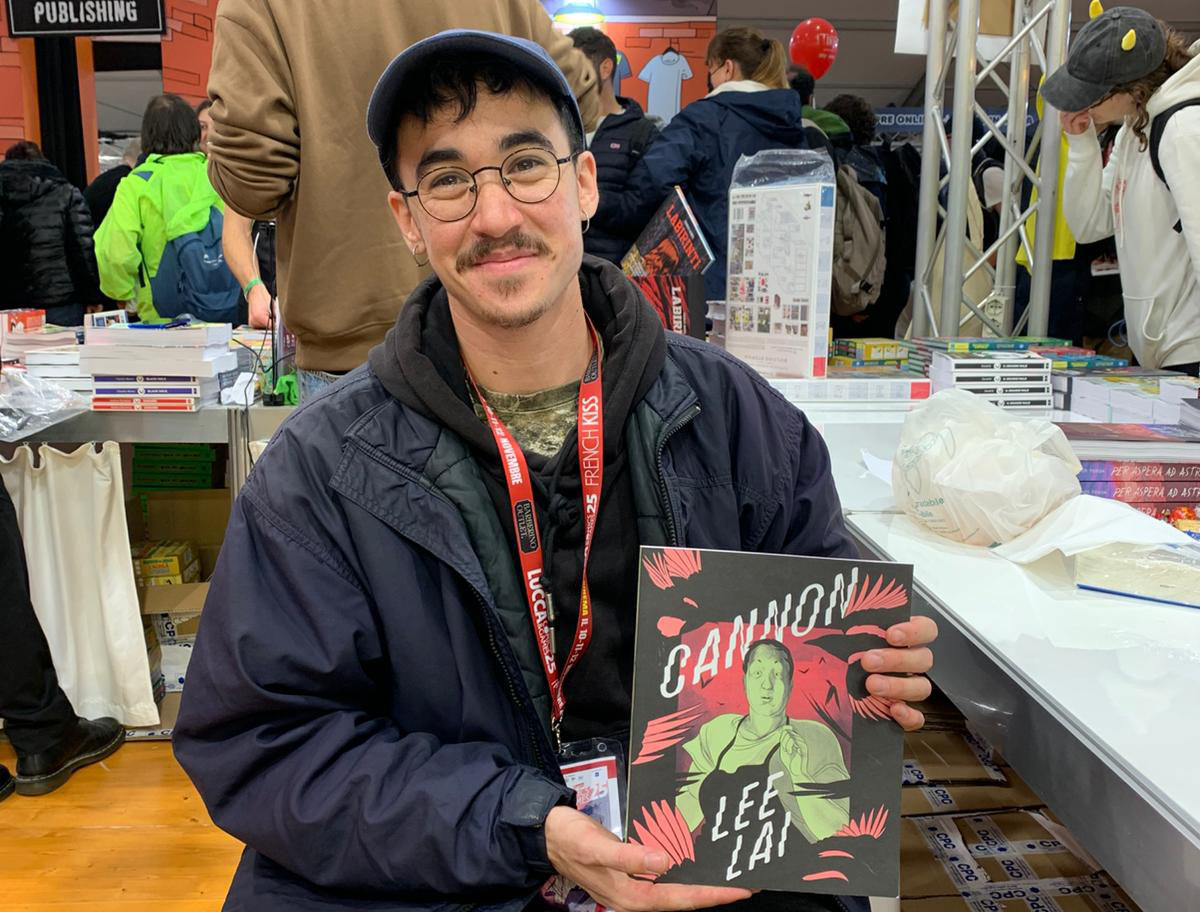

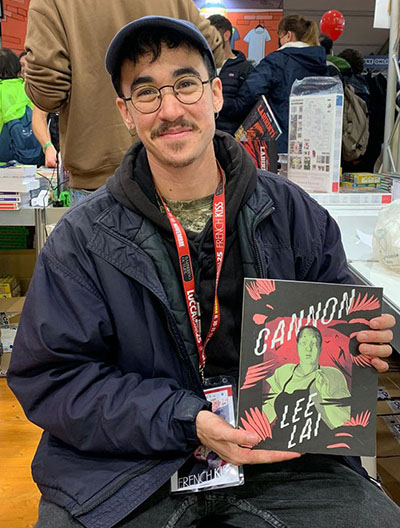

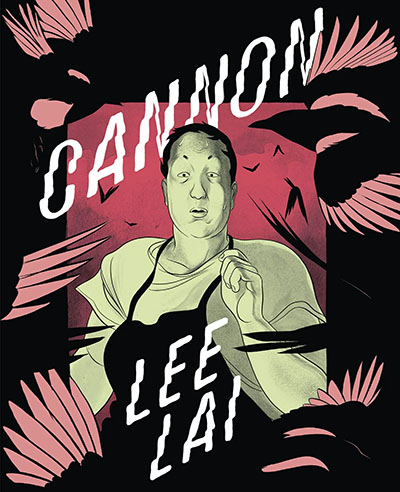

After a shower of nominations (and two Ignatz Awards plus a Cartoonist Studio Prize), Lee Lai returns in 2025 with Cannon, the story of a queer young woman of Asian descent who works in a chaotic kitchen, struggling with a complicated relationship with her mother and her ailing grandfather, a sleazy restaurant owner, a friend who can’t fully listen to her, and her own inability to express frustration and emotion.

As a guest at Lucca Comics & Games 2025, where she premiered the work, published in Italy by Coconino Press, we interviewed Lee Lai about her creative journey and her works.

Hello Lee Lai, and thank you for your time. First of all, I’d like to ask how you came into contact with comics, and how you decided to choose this medium to tell your stories.

I read comics when I was a child: the classics, like Peanuts by Charles Schulz and The Wizard of Id di Brant Parker e Johnny Hart (in Italia su Linus e Urania, ma anche in volumi Mondadori con il titolo Il Mago Wiz, NdR). I loved them, but I didn’t think about it much beyond that. I actually wanted to make children’s books and I kept drawing all through my childhood and into my adolescence. When it came time to figure out what I was doing with my life, I went to art school because that was what I knew how to do.

But I soon found the fine art world repellent, I think it was the class dynamics and the way patronage worked. It just wasn’t for me, socially.

I missed the storytelling aspects of creativity, so I started learning how to write. Around 2014, I began pursuing it more seriously. And now it’s been a decade of working exclusively in comics and that’s been a joy.

Were there any stories or works that inspired this choice — perhaps even by Australian authors, the country where you were born and raised?

One comics artist in Australia that I really looked up to was Mandy Ord (il suo libro più famoso è When One Person Dies the Whole World Is Over, NdR). She’s a bit older than me, and she would do daily-life style comics, like slice-of-life stories. I’d never seen anyone make comics like that before. I found that very inspiring: she would draw herself with just one eye instead of two, and she was also queer, which was exciting to me.

Another cartoonist was Bruce Mutard. His work is much more refined, more polished, but his stories were serious: until then, I only knew comics as funny, which is great (I love comedy too), but seeing stories that were more emotional and darker in nature was really interesting.

But the comic that truly changed the game for me was Blankets by Craig Thompson. I think I read it when I was 15, by that time I’d never read anything so sensitive.

In your stories, you talk about many issues that are dear to you — gender identity, sexual orientation, but also cultural identity. You were born in Australia, perhaps the country where multiculturalism is most present, and your origins are Chinese. It seems to me that in recent years, comics have become one of the main media for discussing these issues, in a very different way — more so than film or literature. Do you see the same trend? And if so, what do you think makes comics so suitable for addressing these topics?

In your stories, you talk about many issues that are dear to you — gender identity, sexual orientation, but also cultural identity. You were born in Australia, perhaps the country where multiculturalism is most present, and your origins are Chinese. It seems to me that in recent years, comics have become one of the main media for discussing these issues, in a very different way — more so than film or literature. Do you see the same trend? And if so, what do you think makes comics so suitable for addressing these topics?

That’s interesting, I hadn’t thought about it in comparison to literature or film. I see a lot of different treatments and different styles of exploring the same themes.

But I think there’s something about comics that’s really indispensable: there are certain kinds of lived experiences, whether that’s having an immigrant family, or gender dysphoria, or anything complex and hard to explain simply, where having both words and pictures, separately and together, gives you unique tools to express emotions and ideas.

It’s less about saying “this is how this is.” Because I don’t want to speak for an entire experience, as I have one version of it, my friends or family have others.

There’s no universal immigrant experience, no universal gender-transgressive or queer experience. Comics give you so many different elements to work with that you can navigate nuance with sensitivity, without being too didactic or simplistic.

Before talking about your individual works, let’s talk about what they have in common. There are many references to issues close to your heart, which also reflect your personal experience — but these stories are not autobiographical, unlike many works dealing with similar themes. You move in the world of fiction, with intertwined characters and stories that are plausible but not true. How do you choose this type of narrative instead of autobiography?

I think memoir and autobiography have a strong tradition in comics, there are so many seminal works in that form, and they’re very inspiring to me.

But I’m just not interested in memoir at all, it feels too vulnerable. I think I’d end up flattening or skirting around details to avoid embarrassment. Do you know the book Stone Butch Blues? It’s a classic American queer story about a working-class butch, a gender-transgressive person who experiences a lot of violence. Many of those experiences are similar to those of the author, Leslie Feinberg, but she said she couldn’t make it autobiographical because it wouldn’t be emotionally true.

And I really understand that feeling. In many ways, I can write stories that are more emotionally honest and vivid because they’re fictionalized. That way, I can take emotions that are real to me — the agony of a breakup, conflict with a family member — and express them truthfully without betraying myself or my loved ones. The ethics of writing about real people in your life? It is a very complicated topic.

Your comics are set in reality, a fictional reality, but still reality. Yet in each of your works there’s a strong metaphorical, even fantastical element that transforms the characters’ world and adds layers of unspoken meaning to the story. Where does this way of storytelling come from?

I think there are a lot of authors who use magical realism and I find that very inspiring.

A lot of my stories are essentially psychological portraits, they’re more about the internal world of the character than the external one. The story is about psychological development, and that can be very internal, even boring, sometimes. Having elements of the uncanny or strange allows emotions, which are intangible, to become physical. It makes the book a little sillier or stranger, and that interests me.

Let’s talk about Stone Fruit, your debut comic, which was a huge success with both readers and critics. What do you think appealed to so many readers and fans? What was the element you most wanted to convey?

Let’s talk about Stone Fruit, your debut comic, which was a huge success with both readers and critics. What do you think appealed to so many readers and fans? What was the element you most wanted to convey?

Judging from experiences at signings and meeting readers, a common thread seems to be that people have strong feelings about childcare, families of origin, and chosen family. The relationship between the child, the aunties, and the mother seemed to resonate with readers.

And, of course, most people have been through a breakup or divorce, they’d share those stories with me, which was very touching.

Heartbreak is universal. Most people can relate to that feeling, and I think Stone Fruit carries a lot of it, and I think that meant something.

It’s beautiful when readers recognize themselves in a story you’ve written and drawn, they see elements of their own lives in it.

I think for an author, that’s the best compliment: when people relate in some way to the story, even if they don’t share the exact experience of the character.

In Cannon, and we’ll discuss it more later, one of the main themes, for me, is communication in personal relationships. In Stone Fruit, the theme is care, expressed through justice, words, but also through simple presence within relationships that can be complicated, as in the conventional family you depict. How important is it for you today to talk about this issue, even in fiction?

I think communication is a form of care. It feels like, in this day and age, we’re struggling to connect more than ever. There’s less of what I’d call social infrastructure to support people simply being in the same space. But that’s something we still need as humans, as animals, really. We need touch, presence, words: all ways of confirming that we’re connected and there for each other.

The characters in both stories struggle to know if that connection is real, if they’re secure in it. I started writing Cannon before the pandemic, and then the pandemic happened: suddenly, writing a story about the decline of a friendship took on a whole new meaning. We couldn’t see or touch our friends. I rewrote the story quite a lot with that in mind, to make it more about these two characters constantly trying, and often failing, to reach each other.

In Cannon there’s a noticeable evolution in your style. The use of monochrome is much more restrained, and your line has become softer, whereas in Stone Fruit there was a more nervous energy. How have you worked on your style over the years, and how does it fit into this new story?

For most cartoonists, I think, style is both intentional and unconscious. This book was drawn over four years, and from the start to the end, the style changed enormously.

Part of it is about tools: I changed my brush slightly, and that changed the line. I’m always trying to get better, I’m never fully satisfied with my cartooning.

There’s always this desire to improve , but what “better” means keeps changing: sometimes it’s about expressing complex emotions in fewer lines, sometimes it’s about perspective, like how good my sense of space is in a room. Setting Cannon largely in a kitchen was a challenge: so many characters, lots of spatial dynamics, visual chaos. I wanted to reduce that visual noise deliberately, to make it simple, not too hard to look at.

Curiosity is also important, because you have to keep moving forward and not get stuck.

Exactly. We do get stuck, we learn to draw something a certain way and keep doing it forever. But I want to keep learning: I’m not very invested in my career in terms of “product,” but I am deeply invested in learning. Each book offers new challenges to learn from, and that’s fundamental to me.

One of the elements I liked most in Cannon is the use of speech balloons. The protagonists’ balloons are often crushed under those of other characters, emphasizing their submissiveness and the general lack of communication between people who don’t listen. In other cases, the balloons expand and almost fill the page during moments of excitement or confrontation. This makes me think Canon also speaks a lot about communication between people. Is this a reflection you can relate to? And if so, did you work consciously on this aspect?

Yes, to a degree I did work on it. Ultimately, those choices just felt obvious: if something is big and loud, it becomes physically big. The experience of being constantly interrupted feels claustrophobic, so that visual compression felt intuitive. It was the best way to show someone being talked over all the time.

So much of the book is about her not having a voice, and speech bubbles are just so fun to play with: it’s so strange and delightful that speech becomes a visual bubble.

In classic comics, you see someone talking nervously or passionately thanks to how the edge of the bubble or the density of the line changes. It’s amazing how universally people understand that across languages and cultures: there’s something almost semiotic about it, like a wobbly line meaning anxiety, or a bold one meaning force. Those things are fun to play with, and they help express tone and rhythm in dialogue, which matters to me as a writer.

Another important aspect — almost a metanarrative one — is your reflection on writing itself: on telling one’s own stories and those of others, embodied by the character of Trish, a successful writer and a kind of best friend who appears confused but also self-focused. During the story, she makes choices that parallel yet oppose Canon’s. in a sort of double coming-of-truth narrative. She’s a multifaceted character who provokes contrasting feelings in the reader. How did Trish come about? And how important is she in your reflection on the role of stories?

I think in many ways, both Cannon and Trish are manifestations of my anxieties about being a friend, because, in some ways, Trish is the bad friend, right? But in other ways, Cannon is the bad friend, because she doesn’t advocate for herself or voice her concerns. That’s something we have to trust our friends with: if there’s a problem, you say it, and you work it out. Cannon avoids that completely. They’re both bad and good friends in different ways, they challenge and encourage each other to grow.

As for the writing element: my work is fictional, but I use many elements of my own life: breakups, hard friendships, complicated family relationships, aging grandparents. These are all real experiences that I want to explore, so I think deeply about my responsibility, both to the people whose experiences I draw from, and to the readers.

I’m constantly asking myself those questions, and talking to friends to find where the red line is and how not to cross it. I don’t think the answer is to avoid drawing from life; we must use our experiences to tell true stories, even if they’re fictionalized.

But there are real ethical concerns when you take from life, especially when publishing to a large audience. Before Stone Fruit, I didn’t have to think about that as I was making tiny comics for a tiny readership. Now the work is out in the world — published, reviewed, discussed — and that means I hold myself to a higher standard of responsibility in my creative decisions.

Thank you very much Lee Lai!

Interview performed at Lucca Comics and Games 2025

Thanks to the Coconino stuff for the support

Lee Lai

Lee Lai is an Australian cartoonist living in Tiohtià:ke (known by its colonial name Montreal, Canada). In 2021, her first graphic novel Stone Fruit was nominated for the Stella Prize and won several awards, including the Lambda Literary Award, two Ignatz Awards and a Gran Guinigi at Lucca Comics. Her comics have been published in magazines and newspapers, including The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, The New York Times, Granta and Magazine, the MoMa magazine. Cannon is her most recent graphic novel.

Lee Lai is an Australian cartoonist living in Tiohtià:ke (known by its colonial name Montreal, Canada). In 2021, her first graphic novel Stone Fruit was nominated for the Stella Prize and won several awards, including the Lambda Literary Award, two Ignatz Awards and a Gran Guinigi at Lucca Comics. Her comics have been published in magazines and newspapers, including The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, The New York Times, Granta and Magazine, the MoMa magazine. Cannon is her most recent graphic novel.