In recent years, Chip Zdarsky has established himself as one of the most important contemporary American comic book creators, moving fluidly between superheroes and creator-owned projects, and between working as a writer and as a full author. Over the past five years, he has written highly talked-about runs on major characters like Batman and Daredevil, as well as acclaimed creator-owned series such as Public Domain and Afterlift. He has also been one of the cartoonists to embrace Substack—the newsletter platform that, a few years ago, shook up the American comics scene—with the greatest enthusiasm.

Through that channel, he maintains a fun and unexpected connection with his readers, creating projects like the manga-focused podcast Mangasplaining and a PDF magazine packed with news about the U.S. comics industry. At the same time, he continues to be a major presence in mainstream comics: a few months ago, he became the writer for the relaunch of Captain America (drawn by Valerio Schiti), and this December he will release the one-shot closing the One World Under Doom event. And just a few days ago came the news that in 2026 he will write Armageddon, Marvel’s next big annual crossover event.

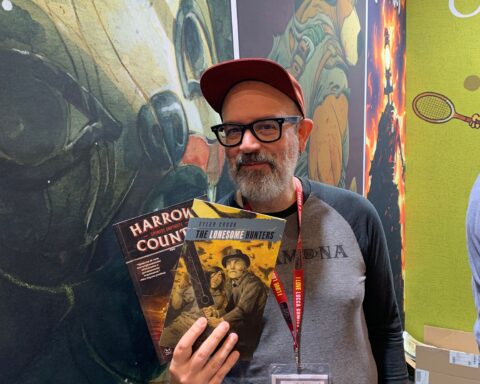

October has been an intense month for Chip, as he embarked on a European tour that took him to London’s MCM Comic Con, then to Walt’s Comic Shop in Berlin (which seems to have caught the event fever after last month’s success!), and finally to Lucca Comics & Games 2025, as a guest of Panini.

It was during these last two stops that we caught up with him for a chat about his past work and his current Captain America series.

Hi Chip and thanks a lot for your time! You’ve worked, and still work, both as a full author and solely as a writer, for major publishers as well as independent ones like Image and the very young DSTLRY. Could you tell us what, in your view, are the main differences in method and approach to production between these experiences?

Regarding the major ones, obviously I don’t own the characters at Marvel and DC, which is good and bad. The good part is, if I’m writing a story and I want to have emotional impact, I’ll get more of a reaction from the reader if I hit Aunt May with a bus than if I hit an old lady with a bus in my Image book, and that’s because in creator own you have to spend extra time building up the connection between the characters and the reader, whereas with Marvel and DC, it’s already built in. If you do something to the characters, people have the history with them, so the impact is greater. The downside is, you don’t own the characters. When you’re done with the book, off you go…you get paid for the job, and that’s it.

Whereas on my creator-owned stuff, I own it with my co-creators, and we have a lot of freedom, so we can do a lot more with those characters than we could with, let’s say, Spider-Man or Batman. There’s freedom, but you have to spend more time building those characters because they didn’t previously exist.

You’re both a writer, of course, but also an artist. Do you have a preference between the two experiences?

It kind of depends on my mood. I will say writing is easier and faster, so I like that part of it. But with art, there’s a greater sense of satisfaction when you finish a page. With writing, you’re never fully satisfied because it still has to go through so many steps afterward, whereas with art, you finish a page and it feels great.

There’s also the nice thing where, when you’re a writer, people can get mad at you for the story, or love you for it, and that can change drastically and quickly. Whereas with art, if someone liked my art on issue 12 of Sex Criminals, they’ll probably like it on issue 13 as well. There’s consistency there. On the other hand, you can love a writer one week and hate them the next because they’ve done something to a character you don’t agree with. So I like the consistency of being an artist, where you know where you stand with the reader. With writing, it feels like landmines every time you start a new project.

Probably only a professional writer like you can say that writing is easy and fast.

To draw a comic takes me a month and a half. To write a script, it takes me about a week. So you can definitely do more, and there’s satisfaction in moving from project to project.

I always feel bad for an artist because when they agree to do something, that’s their life. On Sex Criminals, that was my life. I knew those characters. I spent so much time with them. Matt, as the writer, he knew already the characters, but came in and out—he’d come in when a script needed to be written, then disappear until it needed lettering or notes. But I spent every day with those characters, thinking about them a lot. So the artist really embodies the characters more than the writer, I think.

Speaking of your superhero work, you’ve now written almost all the major characters for both DC and Marvel. In particular, you’ve produced many Spider-Man stories in different moments and formats. Beyond your frequent effort to connect with the characters’ editorial history, with Spider-Man you’ve also created stories that deeply examine and reinterpret elements of that very history—like Spider-Man: Life Story or Spider-Man: Spider’s Shadow, where you explore what might have happened if Peter had kept the symbiote.Are these stories the “Chip fan” revisiting what he loved as a reader?

Yeah, definitely. You can’t work on these characters without having nostalgia for them, it’s why you’re working on them. If you just explained what Spider-Man was to me and asked, “Do you want to write it?”, I’d probably say no. But growing up with it, you have those voices of the characters in your head. Writing professional comics for Marvel and DC is basically writing fan fiction, except you get paid and you get the notes, you don’t get those when you are doing fanfic (laugh).

In your run on Daredevil, I was struck by the fact that it opens with Matt accidentally killing a man—a small-time criminal. I was thinking that maybe a superhero killing someone would have shocked readers more in the past, but today maybe not so much. Superheroes used to have a strict “no kill” rule, not even by accident. Do you think that’s still true today? Can superheroes kill and what does it mean?

They never do it in cold blood. Even a character like Spider-Man has accidentally been involved in deaths before (he refers to that during my Daredevil run). These characters have been around so long that there are definitely storylines where maybe they didn’t save someone or inadvertently killed them. But you’ll never read a comic where Spider-Man decides to kill someone and does it.You can’t undo that. And companies rightly want to protect the characters; crossing that line without a way to undo it would define the character permanently. That’s the danger.

What struck me was the awareness—in that scene with Jessica Jones and Luke Cage, where they say, “That’s part of the job. It happens.”

It’s kind of like being a paramedic or a doctor: you can’t save everyone. Sometimes you make a mistake while doing the job and someone dies. That’s part of it. But Matt is the one with all the guilt. That’s how I write him, that’s how most people write him.

Well, he’s Catholic after all.

Exactly—gotta lean into the Catholic guilt of the character.

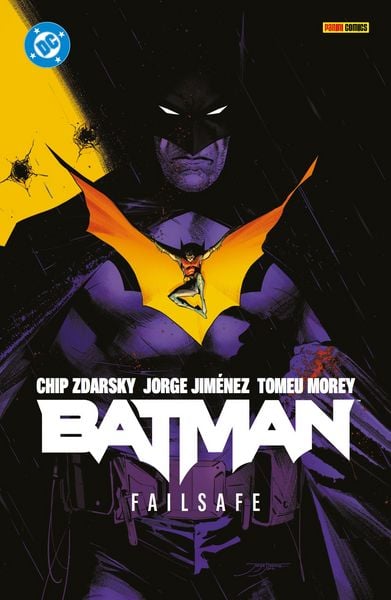

Let’s move to your Batman run. Your Batman includes many references to the character’s mythology—Grant Morrison, of course—but overall, it feels like an attempt to encompass everything that defines the Dark Knight: from Adam West to Michael Keaton, the Arkham Asylum games, the animated series, Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, and more. What was your idea in bringing together so many legendary Batmen, beyond simply paying homage?

One amazing thing about Batman is his versatility: you can have multiple versions existing at once, and it works. There are not so many characters that allow that. I love that you can have a goofy Adam West version, Robert Pattinson, The Dark Knight Returns, or the Neil Adams swashbuckler.

It was hard to decide what mine would be when I started. I leaned more into Grant Morrison’s “Bat-God”—the idea that he can do anything—partly because it’s the main Batman comic, and you want to see him at his best. But being able to do a multiversal story and touch upon other Batmen enhanced that idea of him being the Batman, the one who solves everything at the end of the day.

You did something similar with the Joker, who’s even more delicate to handle, especially when addressing his origin, as you did in Joker: Year One. There are references to Morrison, Moore, and The Killing Joke. Who is your Joker? Is he insane, super-sane, an übermensch, simply evil or something else?

That was the fun part, making him all of those. We reveal that he also went down the Zur-En-Arrh route, splitting his personality but never stopping it. For me, it was fascinating to see how Tom King wrote the Joker, how different that was from Scott Snyder, who was directly before him. I wanted to explain that a bit.

Batman has some variety, yes, but in the end he stays mostly consistent. The Joker on the other hand changes a fair amount. My editor suggested maybe resolving the “Three Jokers” idea, and I thought having one Joker with multiple personalities, rather than three separate ones, would be more interesting. That was fun and a way to reconcile the differences.

Yeah, it’s part of the Joker, this ability to recreate himself. Of course, these character changes happen over time; they’ve been around almost 100 years now.

It’s true, yeah. Maybe I got too deep into it, maybe it was a question that didn’t need answering. But since the “Three Jokers” of Geof Johns and Jason Fabok was not in the main continuity and then it was somehow brought up also in the DC continuity, I liked taking it as a challenge to explain it a bit. Writing comics often feels like solving a puzzle, taking all the pieces and figuring out how they fit.

What was your biggest challenge in handling these characters? Or would you have done something differently, especially with Batman or Joker?

I can’t think of anything major. You do the best you can with what you’re given, working with various artists and dealing with the inner workings of a company. At the end of the day, you did the job, and hopefully you’re happy with it.

I’ve been lucky, I haven’t had a job where I thought I couldn’t tell the story I wanted. I’ve heard horror stories, but generally, the story I want to tell is the one that ends up on the page. That’s satisfying.

If I have one regret, it’s scheduling: I mean, sometimes I wish we didn’t need fill-in artists sometimes. I love working with everyone on Batman, but if Jorge could’ve drawn the whole thing, that would’ve been amazing. Same with Daredevil and Marco. We had great guest artists—Mike Hawthorne, Jorge Fornés—but a consistent style would’ve been nice.

You have recently become the author of Captain America, whose first Italian issue is being presented here in Lucca. A hero with a very special significance and value. What does Captain America represent to you, even as a Canadian? And which of the many versions inspired you most, or which one are you most attached to?

I grew up reading the character. Being Canadian and living across from America, you’re very influenced by it, as most of the world is.

I really gravitated toward the 1980s Captain America when I was younger—the Mark Gruenwald and Kieron Dwyer run. What fascinated me was that storyline about him giving up being Captain America. It really drove home who Steve Rogers was, and that he wasn’t Captain America. He wasn’t America. He represented what he wanted America to be.

And I think that’s the important part of the character, the tragic nature of Steve Rogers. The tragedy is that he wants America to be better, and it never will be what he hopes it to be. So he’ll always have to fight for freedom and democracy, because those ideals are always in danger.

I mean, we see it now, right? (laugh) So yeah, I loved those comics as a kid. I also love Mark Waid’s Captain America run, Ed Brubaker’s run, and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ run.

There have been so many great Captain America stories, and at the heart of them all is the sad nature of Steve Rogers. For some reason, I’m always drawn to sad characters.(laugh)

The first issues of your Captain America are very dense in structure. Part of the story is set in the past, part in the present. They manage to touch some of the raw nerves of American society—its radicalization and its most recent history, especially the post-9/11 period. How did you reason through this choice, and how did you work on creating a new Captain America born from that very context? How did you decide to divide the story between the recent past and the distant past?

When I started thinking about Captain America, I realized I wanted to tell the story of him coming out of the ice. Part of that was because I began thinking about how time is represented in Marvel comics. With the sliding timeline they use, he would have come out after 9/11, it’s been too long otherwise. He absolutely would have emerged in that era. So that got me thinking: what would that mean for the story? Considering September 11th and the surge of patriotism that followed, it seemed there must have been a Captain America during that time. In previous comics, they had a Captain America in the 1950s after Steve Rogers. So if they did that then, something similar must have happened after 9/11. That’s what set me down this path.

I really liked the idea that when Steve wakes up, for him it was just yesterday that he was a soldier in a war, and today, he wakes up and he’s still a soldier. So the first thing he would do is go back to base, check in with the generals, and find out what’s happened, where he is, and how he can be of service. He wouldn’t immediately join the Avengers, as it was originally presented. So having those two parallel stories—one in Afghanistan and Iraq, the other in the modern day—seemed like a great opportunity to contrast those experiences.

When creating this structure, did you also think about how Valerio Schiti, who designed the new Captain’s look, would interpret it? How did you work together?

Both Valerio and I relied a lot on Frank Martin, the colorist, because we knew the easiest way to distinguish time periods was through color palettes. The pages set in the past aren’t quite sepia, but they’re more subdued, so they feel like a different era from the brighter, modern-day scenes. We relied heavily on Frank for that, knowing that it might otherwise confuse readers. But I didn’t want to hold their hand through it. I wanted them to maybe finish reading and think, “Wait, did I get everything?” and then go back and reread.

One thing Marvel and also DC tend to do too much is hold readers’ hands. They have rules, like: if you start a new scene, you must include a caption saying where you are. If it’s a different time period, you must include a caption saying when. So I had to convince them that I didn’t want that. I didn’t want the first page, showing the Twin Towers coming down, to have a caption saying “September 11, 2001.” Readers would figure it out.

But yes, Valerio’s work is beautiful, and Frank really helped separate the time periods visually.

Still on Marvel, in December, the one-shot The Will of Doom will be released, closing the event that has just begun in Italy, One World under Doom. The word “Doom,” or “Destino” in Italian, also ties to the main antagonist in Cap’s earliest stories. In general, your history at Marvel is closely linked to this character and to the Fantastic Four—you even visited the set of the movie. What fascinates you about this group, and about Doom in particular?

I love the Fantastic Four because, unlike most other teams, they essentially stay the same. It’s the same four characters. You’re following that core cast, Marvel’s first family, so they carry a special weight. And also, they’re not superheroes in the traditional sense; they’re adventurers and explorers. I think that’s amazing, that Marvel’s whole universe grew out of this group of explorers.

But Doom is my favorite villain. Writing his voice is so fun. He has the perfect tragic backstory for a villain. And as you’ll see in One World Under Doom, he’s also right. In many ways, that story is about one person taking control of everything and actually making life better for people, even though it denies them their freedom. It’s about the allure of fascism that’s built into that character, which I find fascinating.

There’s also the tragedy of someone so brilliant that he could solve every problem, if only his ego didn’t get in the way. I love writing that character. Even beyond the first chapter of Captain America, Doom will keep popping up, because he’s just too fun not to write.

First Batman, then Captain America—two icons of American superheroes, but also two character archetypes that are similar in some ways and opposite in others. From a writing point of view, what are the differences in your approach to each of them?

I find them to be very different characters. Batman is sure of himself, he makes plans, and he executes them.

Cap, on the other hand, is sure of his moral center, but unsure of how to create change or how to effectively help people and put forward his ideals of freedom and democracy.

I’m sure Batman cares about freedom and democracy, but that’s not his driving goal. His goal is to prevent what happened to him from happening to others, whereas Steve has more empathy, he feels deeply for people in those situations.

You continue to create Public Domain, which you distribute on your Substack and which has been collected in volumes by Image Comics. In this story, alongside your deep character work, you also explore the U.S. comic book industry—its more disenchanted, even toxic aspects. It feels like a comic that distills everything you’ve done so far, moving between drama and comedy, the everyday and the extraordinary. How did the idea come about? What drove your need to tell this story, and how much did the absolute freedom of the platform help you?

I’ve always had absolute freedom working through Image Comics too, so that wasn’t new when I did it on Substack. The idea actually came from a podcast I co-host, called Mangasplaining with some friends, where they explain manga to me. We’ve read hundreds of titles, and I’ve learned a lot. One big takeaway for me was that I love books where creators write about real things. Ping Pong was one of my favorites, it’s literally about ping-pong players. There are manga about rice, about radio DJs, about jazz.

In the North American comics market, it’s almost always genre-focused. The pitches are like, “It’s cowboys meets outer space,” or “It’s medieval times meets zombies.” Always mashing genres together, which, frankly, is boring. I’m guilty of it too; I once did superheroes and vampires.

But I love stories about things people are passionate about. And I realized, sadly, that what interests me most is the comics industry itself: i read lots of interviews, I like the history of comics, its behind-the-scenes stories. So I knew I wanted to tell a story about a family and the comic industry. It’s not based on my life, but I do have insider knowledge. I love stories about people: no one in the book has powers or anything, it’s not fantastical, except for the fact that the creators will get their rights back. This is the only imaginary thing, sadly (laugh).

Still on the subject of Substack. A few years ago, it was presented as the platform that would save comics in the wake of the pandemic. It seems that after an initial surge, it has slowed down, but it still offers an important space for many creators. Yours is honestly one of the most entertaining to follow—and also one of the cheapest. It’s interesting because it’s allowed you to expand your relationship with readers through things like Mangasplaining, and more recently you’ve started producing a very informative PDF magazine on the U.S. industry, along with interviews with colleagues and reading recommendations. How do you work on this newsletter? And in particular, did the latest magazine begin as a kind of self-promotion?

The magazine came about because I hate the Internet. I have my Substack, but that’s all—I’m not on Twitter, not on Instagram. I quit all of that.

So I found myself thinking, I still need to promote my work, but how do I do that? And I realized comic shops are the best place. So I printed a physical magazine, 50,000 copies and sent them out for free to comic shops across North America.

And I really enjoyed doing it, so I just kept going. My background is in journalism and design, so putting it together is a lot of fun. That’s the reason I started, and I’ve continued because I enjoy it. It’s a lot of fun to make.

Last question about your creator-owned works: the latest that came out is White House Robot Romance for DSTLRY: what’s the idea behind it? Can you tell us something about it?

Again, like I said for Public Domain, I think I’ve just been reading too much manga due to my podcast. And I realized I especially loved quirky yaoi and boys’ love titles. I wondered if I had a story like that, something weird, fun, romantic, with comedy and action.

I like stories that cross genres—sci-fi, romance, comedy, action—all in one. It began as a desire to tell a romance comic, weirdly, and I kept adding fun layers. Then I pictured Rachel drawing it and thought, “I want to see this in the world.”

The DSTLRY format is beautiful: the size, the packaging, the length. Being able to tell a full story in three 45-page issues was very satisfying.I did the same with the series Time Waits and it is always beautiful to see that all done in the end.

In the robots, they’re very genuine—but they kind of remind me, visually, of those TV-headed robots from Saga.

Yeah, I can see that. Just kind of blank.Saga is a huge inspiration, not just for me, but for almost everyone in the industry. It shows that if you just make the thing you want to see in the world, it can work. Brian and Fiona said, “Let’s make a comic for ourselves and see what happens.” And it became Saga.

Sometimes those are the best projects—when you write what you’d like to read.

Yeah, I always end up writing or drawing what I want to read. Sometimes other people want to read it, sometimes they don’t, but either way, it’s a success because it’s the thing I wanted to make. That’s always nice.

Thank you again for this interview(s), Chip!

Interview done on November 28th at Walt’s Comic Shop in Berlin and on November 31st at Lucca Comics and Games 2025

Thanks to Walt’s Comic Shop, Panini and Goigest stuff for the support

Chip Zdarsky

Under the pseudonym Steven Murray, in the finest superhero tradition, he has written a whole bunch of stuff for a whole bunch of publishers, from superheroes to creator-owned work.

I could make a list here, but it would be way too long, so I’ll just mention Daredevil (mainly with Marco Checchetto), Batman (mainly with Jorge Jimenez), and the recent relaunch of Captain America together with Valerio Schiti, as well as Public Domain.

If you want to have fun and get some good laughs, besides reading what he writes in comics (but not the dramatic ones, only the funny ones!), also read what he writes about comics in his newsletter https://zdarsky.substack.com/

I like to think the author might enjoy this biography and maybe even admire my laziness in not looking for an official one. No AI was used to write these lines, though maybe one would have done a better job.