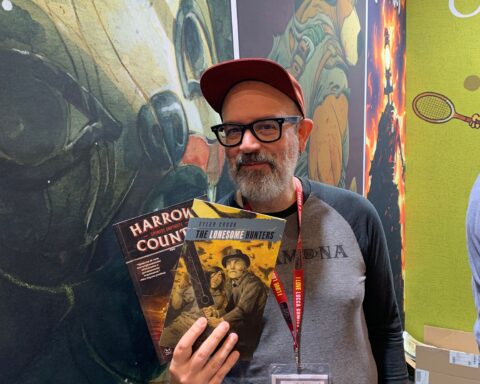

In recent years, Christian Ward has become one of the most celebrated illustrators in the U.S. comics market. With his ethereal, psychedelic style, built on sinuous, liquid lines and neon colors, Ward has made a strong impact both through his creator-owned work (ODY-C with Matt Fraction, Invisible Kingdom with G. Willow Wilson) and through his superhero projects (Black Bolt with Saladin Ahmed, Aquaman: Andromeda with Ram V), earning multiple awards, including several Eisner Awards.

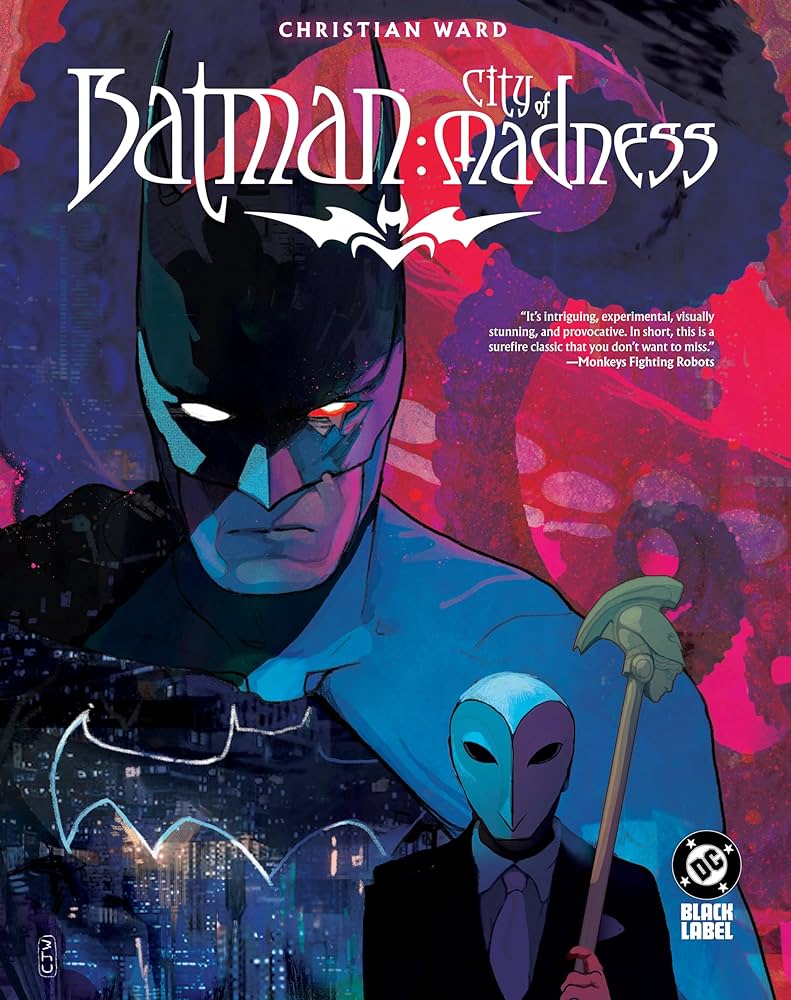

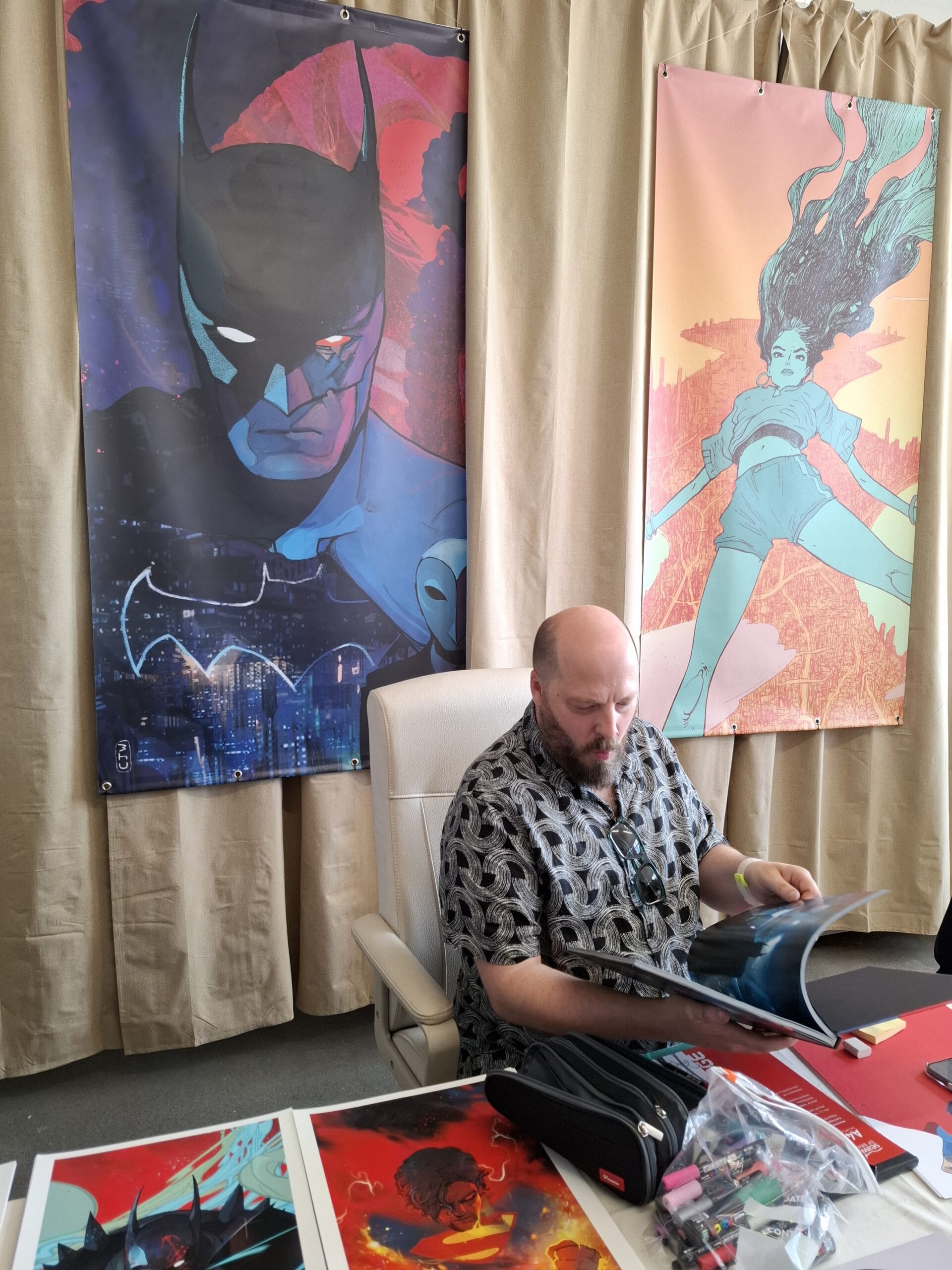

In the last few years, he has helped reshape the world of Batman both as a solo author, in the Black Label miniseries Batman: City of Madness, and in the Two-Face miniseries. We spoke with him about these projects and his broader career during the event organized by the Berlin comic shop Walt’s Comic Shop for its first five years of activity.

First of all, thanks a lot, and I would like to start from your beginning,especially something that I read in your biography on your website, that after ten years of encouraging London teenagers to draw anything other than comics…

So, your secret origins are a little bit different than expected. What was it that brought you to becoming an Eisner Award nominee, actually, a multiple Eisner Award winner?

Yeah, this is somehow funny. I grew up in a place called Wolverhampton, which is in the middle of England, and it was the sort of place where, when you had career conversations with your teachers or anyone in education, if you said, “I want to be a comic book artist,” it was like saying you wanted to be a Hollywood film star, a rock star, or an astronaut. It just wasn’t considered a real job, something people actually did. Even though I wanted to be a comic book artist from a really young age: I used to draw comics, photocopy them, and sell them on the primary school playground when I was eight or nine, it always felt unrealistic.

Reality kind of pushed me in another direction. I moved to London, and anyone who’s lived in a big city knows it can be tough. For years, I was very poor and struggling, so I had to get a “real job.” At that point, being a comic book artist still felt like a fantasy, something that couldn’t actually happen. I became a schoolteacher and to my surprise, I loved it.

I really enjoyed teaching during the ten years I did it. I loved engaging with young people and teaching them about art. But over those years, I kept reading comics. I was a “Wednesday warrior”: I’d go to the comic book store every week and pick up new issues.

This was in the early 2000s, when internet forums were starting to appear. You’d have writers like Brian M. Bendis with their own forums, and I’d post on them. The first big thing that happened was an art competition for Powers, back when Bendis started doing that series.I started doing fan art as part of those competitions, and people responded really well to it. I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting, people really like what I do.”

I had let comics go for a while, but I still wanted to make art. I tried doing children’s picture books, contemporary illustration, and for a long while, I was a fine artist making large canvases and showing in exhibitions. So, my comic art became this strange amalgamation of contemporary illustration and fine art painting, very different from traditional spandex superhero art.

Back in teaching, I worked in Bethnal Green in East London. To engage teenage boys especially, I introduced comics into the curriculum. It was a great way to teach composition, body proportion, and other fundamentals, as you could hide the learning inside comics.

Basically, I was making comics as part of teaching, and at home I was posting my art online. Then one day, a pupil said, “If you’re so good at this, why aren’t you doing it?” That was the penny-drop moment.

People online were reacting positively, I was enjoying teaching comics, and that combination encouraged me to give it a real go. I started putting out more work, and eventually a writer, Brian Clevinger, saw my art and asked if I wanted to collaborate on a comic. I did a project for Atomic Robo, an indie book still going today, and things snowballed from there.

It was really the combination of never letting go of comics as a passion, sharing work online, and engaging students through comics that came together and led me to the career I have now. It’s amazing.

And then your career started. First with creator-owned comics, that really brought you into the public eye and gained more and more attention. But then came the superhero books. What’s the difference for you when working on one or the other? What are the challenges in each?

It’s interesting, because it’s something I’m dealing with right now, the different challenges of each. At the moment, I’m spread between three worlds in comics: creator-owned, DC (as part of the big two), and licensed comics—like Event Horizon—where you adapt something from another medium. I approach each one the same way, my approach is consistent.

That’s not to say I don’t hit roadblocks. For instance, when I was doing Two-Face, there were certain things I wanted to do but couldn’t, not because editors disagreed, but because it’s not my toy to play with. Someone else is also using that toy, and it has to fit. You can’t break it.

Creator-owned work offers more freedom: those are your toys, and you can do whatever you want. But as far as how I approach things, it’s the same. It’s always about telling a good story, making the characters feel real and engaging.

I always try to do two things: one, make the comic entertaining first and foremost; and two, make it about something. It doesn’t have to be weighty, but it needs a core idea. For instance, Batman: City of Madness was about trauma, how we deal with it. Every book I do has that central thread, whether it’s creator-owned, big two, or licensed. It’s all about telling good stories.

Talking about Batman: City of Madness. First of all, were you a superhero and Batman fan when you were growing up? You said you were a Wednesday warrior. And this was a Black Label book, which gives you more freedom since it’s outside of continuity. How was it to work on such a character but with more freedom? For example, you chose the Court of Owls as one of the main villain here, which is not a trivial choice.

I’d say Batman: City of Madness was the best professional year of my life. It was absolutely amazing. The book that really set me on this path was Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth by Grant Morrison and Dave McKean. That book is very important to me, and City of Madness was a pseudo-sequel to it.

When I talked to DC Black Label—specifically Chris Conroy, the editor—about doing it, I was thrilled by how much freedom they gave me. I could do anything I wanted, within reason, as long as it fit the characters. There were things in that book, swings I took,that you couldn’t do in main continuity.

I was so grateful that everything I wanted to do in that book, I was allowed to. No pushback at all. There was a real sense of freedom, excitement, and pride. To write and draw a Batman book, that’s the pinnacle.

I’m so proud of that book and how it came together. Whenever people tell me they love it, it means so much. It was pure joy from start to finish, and I’ll always treasure it. It was wonderful. It’s downhill from here, unfortunately.

The most important part of the title, for me, is City. Most of the recent Batman stories focus a lot on Gotham and Batman’s relationship with it. Your Gotham really reflects your style: it’s a city of neon flares, but it also feels like Christopher Nolan and Joel Schumacher merged together. Was that an intentional inspiration?

In City of Madness, for anyone who hasn’t read it, the conceit is that there are two Gothams: Gotham Above (the one we know) and Gotham Below (a hidden world). I wanted to explore trauma and how Gotham itself is a trauma machine that keeps feeding on itself.

Having Gotham Above and Below gave me visual flexibility. As you said, I could draw from Nolan’s films to make Gotham Above look like a real city,but just slightly off. Actually, I think the film that best captures how Gotham should look is The Batman: Matt Reeves and his production team nailed it. Then Gotham Below is far more baroque and nightmarish, it doesn’t feel real. I wanted it to look like a mashup of different time periods. In a sense, that’s what Batman is: comics from the ’30s, the ’60s, the ’80s, and now, all mashed together. It represents his history and how malleable he is as a character.

He can be campy, a detective, a superhero, all of that. So the city reflects that multiplicity, because Batman is all those things.

Continuing with Batman, you recently wrote a story about one of his most famous villains, Two-Face. In this case, you were only the writer, not the artist. You haven’t done that often, so how was that experience for you? Did you feel like you lost some control over the work, or did it feel freeing to see your ideas represented by someone else?

I made the choice about five years ago, around 2020, to really focus on writing. That was always the plan when I started, I wanted to write and draw my comics. But I got the chance to work with people like Matt Fraction and G. Willow Wilson, you don’t say no to them. I was so lucky to collaborate with amazing writers.

But by 2020, I realized if I didn’t start writing now, I never would. I didn’t have time to both write and draw, and I wanted to be taken seriously as a writer. So, I removed myself as an artist to let my writing stand on its own. I wrote a book called Machine Gun Wizards with Sami Kivelä, an amazing Finnish artist, published by Dark Horse. That ties into Two-Face and another book I did for Image called Bloodstained Teeth with Patrick Reynolds. In each case, I was writing stories that I wasn’t necessarily the best artist for. Those books are all crime dramas, quite pulpy. Fabio Veras, who drew Two-Face, does amazing noir-style art. That book was essentially a courtroom drama, and my art isn’t suited for that, as I tend toward the ethereal, strange, and psychedelic.

It’s about taking your ego out of it. It’s not “The Christian Ward Show.” The story is what matters. If it’s a noir story, I need an artist whose strengths fit that. The story always comes first. The same goes for Event Horizon at IDW. You might think, as someone known for cosmic horror, that I’d draw it myself, but we got Tristan Jones, who’s brilliant at realistic, cinematic art. His architectural detail grounds the story in a way that serves it better.

Especially since that book may attract non-comic readers, I wanted it to look like the film’s world. So again, it’s about following the story, not the ego. That said, I do miss writing for myself, and I’m currently working on something that I’ll both write and draw. But I also love collaborating with artists. There’s nothing quite like seeing someone bring your words to life.

Even though I’m an artist, I’m not immune to that magic of seeing my ideas realized through someone else’s vision. I always make sure not to impose how I would do it. I choose artists I trust, and they’ve never let me down—Sami, Patrick, Fabio, Tristan—they’re all amazing. When you work with great people, you’re always happy.

Then the last question, which probably should have been the first: you’ve talked a lot about your art and other people’s art. What were your inspirations at the beginning? And by working with other artists, do you ever find yourself inspired to try new things or adopt elements from them?

It’s funny: when I started, the artists who inspired me aren’t necessarily visible in my work. I really love Dave McKean and Bill Sienkiewicz, just incredible artists. Their energy and their “anything goes” approach to comics really influenced me. They showed me that art can evoke an emotional response rather than just a narrative one. From a storytelling point of view, probably Frank Quitely, even though our work looks nothing alike. His storytelling is sublime, you can read his comics without any words. That’s a huge influence.

When it comes to working with other artists, I’d say I’m inspired rather than influenced and there’s an important difference. Being inspired makes you want to do your best work; being influenced can lead to imitation. Over the last 20 years, I’ve probably learned more from writers than artists, people like Matt Fraction, G. Willow Wilson, and Saladin Ahmed. By reading their scripts, I learned how to structure an issue, manage pacing, and understand the “real estate” of 20 pages, what’s essential, what isn’t.

It’s quite mathematical, really. You can only have so many panels on a page. How do you tell a story efficiently and emotionally in that space? Those are the lessons I’ve really absorbed over the last 15 years before I began writing myself. So, I’d say I’ve learned more from writers lately, but artists continue to inspire me.

Thanks a lot Christian for your time.

Interview done at Walt’s Comic Shop in Berlin on the 20th of September 2025

Huge thanks to the whole Walties crowd

Christian Ward

Christian Ward is a UK-based illustrator, comic artist and writer.

Some of his clients include Marvel Comics, DC Comics, Dark Horse Comics, EPIC Games and The Guardian amongst others.

After 10 years of encouraging London teenagers to draw anything other than comics, Christian Ward is now a multi-Eisner winning comic book artist and writer. He is best known for his cosmic space operas ODY-C co-created with Matt Fraction and the Einser winning Invisible Kingdom co-created with G. Willow Wilson. He was also the artist on the Acclaimed Marvel comics series Black Bolt (with Saladin Ahmed ), as well contributing to both Thor ( with Jason Aron ) and Batman ( with James Tynion IV). In 2019 he released his first book as a writer, Machine Gun Wizards co-created with Sami Kivelä and then BLOOD STAINED TEETH co-created with Patric Reynolds. In 2024 he released Batman: City of Madness for DC Black Label, in 2025 he wrote Two Face with drawings of Fabio Veras.

Ward currently lives in Shrewsbury with his two daughters, his wife Catherine and pug named Thor.