I don’t care about Superman. And he doesn’t care if I do. The air, Coca-Cola, traffic-jams and procrastinating cable repairmen are not something it’s necessary to have an opinion on; they will always be there, and most of them were humming along before you were here.

And yet whole sections of the economy, the environment, life itself would cave in if these things weren’t in place. Certainly the citadel of superheroes would have nothing to stand on if not for the original character from whom they take their noun. One doesn’t care about Superman because one doesn’t have to. But that’s just one more job he won’t be thanked for.

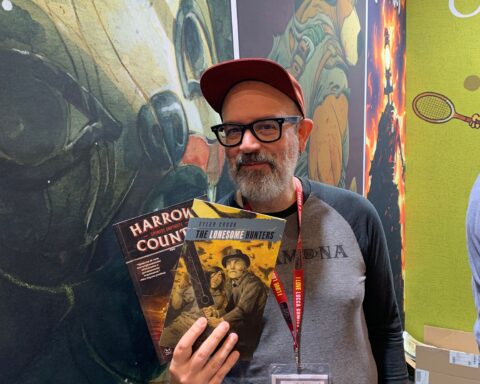

Mark Waid is famous for saying that he was inspired to write comics by the calling of learning that there was one symbolic being out there who, whether he even knew Waid, would always care about him. This was Superman, and of course Waid went on to write one of the all-time most-meaningful Superman stories in Kingdom Come (with artist and co-creator Alex Ross).

Not insignificantly, this was as much a story about how the character had strayed from his roots as it was an affirmation of those beginnings. The Kingdom Come Superman is isolated, embittered, and cast off by a world of heroes who have forgotten how to serve society selflessly. They don’t know better and he does, which makes his alienation the true transgression.

We get the essence of Superman’s altruism, his humility, his ability to be bound by nothing but duty, his sense that his specialness is betrayed if he believes that his importance is singular — we get these qualities in stories set in the past, or alternate timelines, or guises that don’t go by his name at all.

Those runs were intensely conscious of the accumulated canon of the character, something that was supposedly swept clean with the New 52. DC has miscalculated in that housecleaning, at least where this character is concerned — the public knows, likes and depends on a Superman with red underwear who’s married to Lois Lane and is old as hell and twice as wise; America’s Dad. But a dad who’s eternally boyish, too, which keeps him fresh — like most dads, there are some things he’ll always do better than you can and some things you’ll always know better than he does. When most casual readers, or the general audience — those who read a Superman comic once in a decade or go to a Superman movie once in 20 years or watch the perennial TV series or cartoons — when these observers want continuity wiped, they expect it wiped clean to the fundamentals of the character that have hung on over decades. Marvel’s heroes were built to change, but DC’s were meant to gather history, and that’s why they stand as strong as Robin Hood and Hercules.

The theme of Kal-El as repository of an entire planet’s DNA in Man of Steel was thematically true to these expectations (notwithstanding how wayward from the essence of the character many think that movie is) — no matter how young he’s supposed to be with each resetting of the DC Universe stopwatch, we know he always holds within him each era’s version, like quantum coats of paint. This of course also means that the character has ascended to such archetypal status that each era can have its own Superman figure — opening space for Supreme and Samaritan and Hyperion and The Plutonian, and allowing successive eras to project traits of their own onto (and into) Superman himself — another legitimating factor for Man of Steel’s conception.